I've recently come across a number of articles that claim that "customer experience is the new marketing."

After reading those words over and over again, a little idea started to whirl 'round in my head.

I am a firm believer that good marketing focuses on what the potential user already wants to do, not on something that you want them to do. With this in mind, how is this "customer experience" idea something new?

Well, in fact, it's not new at all.

Customer experience is actually the old marketing. "Old" not because it's no longer cool but because it's at the core of fundamental marketing practices. Retail and consumer marketing introjected this idea, not yesterday, but years ago.

Take, for instance, Nordstrom and how they mapped the experience of their customers so that they could continuously support it every step of the way. Think about how JetBlue very counterintuitively redesigned the experience of customers who were flying with them for the first time.

Think about IKEA and the way they have planned the customer experience. Their stores are typically a hassle to get to (especially for city dwellers), and good luck finding a parking spot close to the door. For most any piece of furniture that you buy, you have to assemble it yourself! The entire experience reeks of deprivation. But you also get things you don't expect from a furniture company. Being able to drop your kids off in a clean and brightly lit care center while you shop is just one perk.

Customer experience is the bedrock of modern marketing and it's where marketing itself has its roots.

So, why am I seeing so many articles describing "customer experience" as a new way to do modern marketing?

Aren't they serving the same customers who buy software and cars and all the other experiences that brands are selling us? Aren't those customers humans too?

So why are we hearing all this talk about customer experience as the "new" marketing?

Let's take a step back and define what Customer Experience (CX) truly is.

Customer experience (CX) is the product of an interaction between an organization and a customer over the duration of their relationship. This interaction is made up of three parts: the customer journey, the brand touchpoints the customer interacts with, and the environments that the customer experiences (including the digital environment) during their experience. A good customer experience means that the individual's experience during all points of contact matches their expectations.

This is how Wikipedia defines customer experience: It's the result of the interactions between an organization and a customer over the duration of their relationship.

So, if "customer experience" has always been part of the equation, why is it suddenly being touted as something new?

In reality, this is not new — it's just different.

It's also different from what most businesses do. As customers, we don't like cold calls from sales reps, we hate spammy promotional emails that clog up our inboxes and give us nothing of value, and we hate the idea of someone who's selling to us rather than helping us achieve our goals — not theirs. We hate all of those things, but if you're in marketing or sales, we end up doing the exact things that we hate.

That's why it sounds different.

Before we dig in further, we need to take a step back to understand the world of today's marketing from a broader perspective.

In most companies, marketing people are obsessed with generating more leads, more signups, more downloads, more purchases, more of everything.

In this way, marketing becomes a purely tactical activity with the overriding objective of maximizing leads. Everything is judged through the lead generation lens where more means better.

This whole thinking is completely separated from the customer experience. Instead of thinking about customers, you are thinking about achieving your organization-centric objectives.

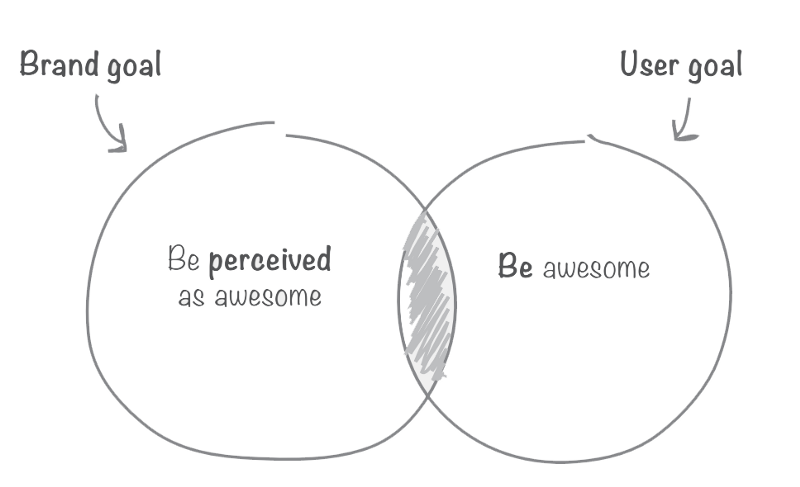

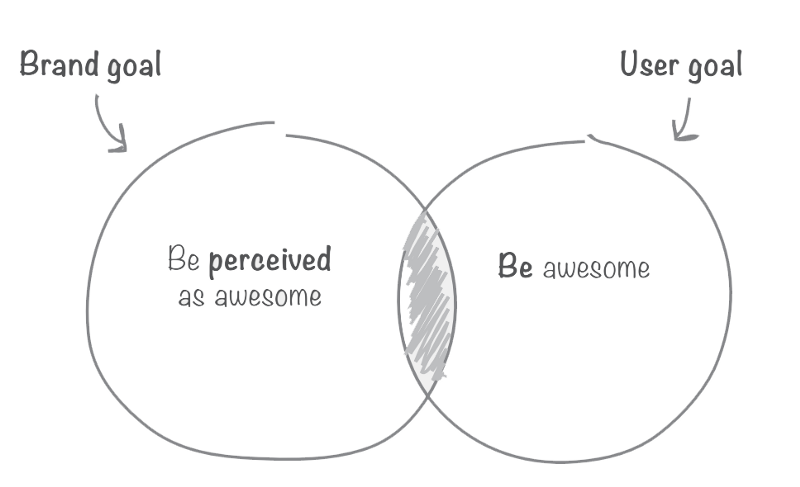

Often, companies' goals and users' goals aren't just different, but mutually exclusive.

Most companies put a tremendous effort into creating awesome marketing materials, super effective landing pages, extremely catchy ads and so on. Paradoxically, when they get money from users, they start paying less attention to the customer and shift their interest to the product.

We get their attention, we get them in front door, but what about after they pay? We consider the "transaction" closed, done, operation terminated, and it's on to the next one.

From that moment on, every experience that the user has with the company is only about the product itself.

Think about it.

After our customer has given us money or has signed on to receive our service, we shouldn't just stop there. Instead, we should focus even more on what our customer really wants to do.

They don't want to be badass at our product. They want to be badass at what they do with it.

It's this shift in perspective that most companies just don't get.

Even if it sounds obvious, it's not.

Most companies are trying to compete on the quality of the product, not on the quality of the user's results with the product.

Customer experience is about two main things: perspective and empathy.

#Perspective: Customer Experience

One of the best examples I've seen recently is from FullStory's Amy Ellis in a lecture at Forget The Funnel.

In this 30-minute video (which I'd recommend watching), Amy explains her thought experiment with the analogy of a dinner party.

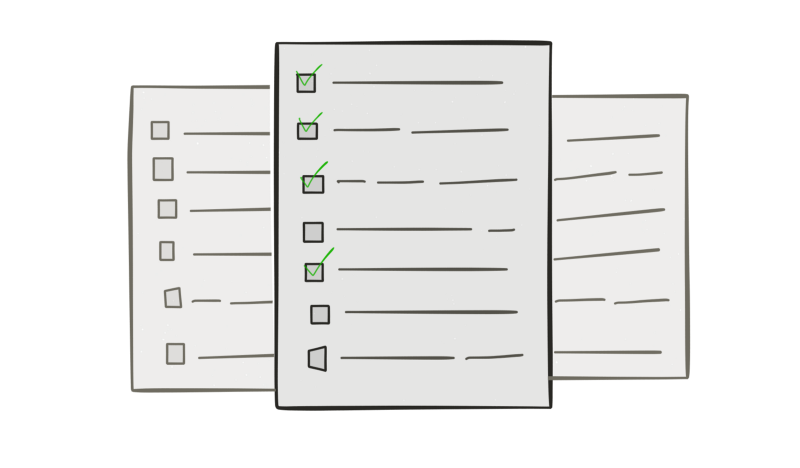

Image that you're hosting a dinner party. You start by thinking about all the things you would need do in preparation for the dinner party, all the components you need to make it happen.

Think about your "thinking" approach: it's a checklist. You break things down into tasks and subtasks.

- How to get the food

- When you need to start cooking each dish

- How you will decorate the table, and where everyone will sit

- What kind of wine you will serve

- Etc..

In making your list, these are all necessary "puzzle pieces" that you'll use to assemble your dinner party.

The problem with this approach is that you tend to give the same importance to all the pieces of your puzzle. If one of them is missing you cannot complete the puzzle. As a result, each item on your list feels equally important.

Time to switch gears. Now, pretend that you're not the host, but one of the invited guests.

Your first touchpoint with the party will probably be an invitation from the organizer. This should answer some of the questions that you probably have, such as:

- When is the party?

- Where is it? (And can I take the bus or the subway?)

- What is the dress code?

- Who else is invited? Will I already know the other guests?

- Do I need to bring anything? Should I also bring a gift?

What will be the next touchpoint and will it answer the other questions that you may have?

- A reminder email or postcard would be useful so I don't forget about the event.

- Is there plenty of parking available or will I need to pay for it?

- Will I be introduced to people I don't know?

- When I get there, what should I do with the gift that I bought — should I leave it with someone?

As a guest, your decision-making process is completely different. It may look something

like this.

What has changed? You're playing a different game that requires a different series of steps.

Like playing chess, you're evaluating combinations for every possible variation. It's no longer about checking tasks off a list, it's more of a thinking exercise.

Now, compare the two scenarios. Details that are important to the host are quite irrelevant for the guest.

To take this a step further, we need to empathize with our user.

Empathy: Customer Experience

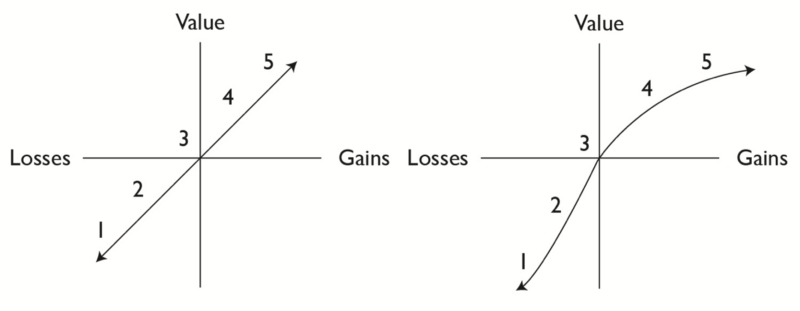

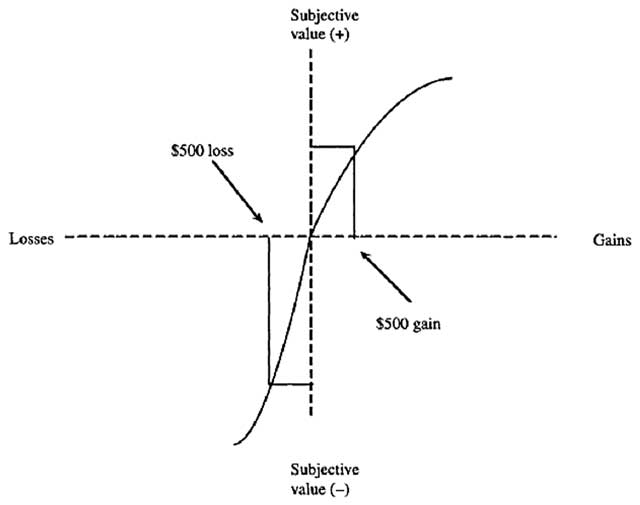

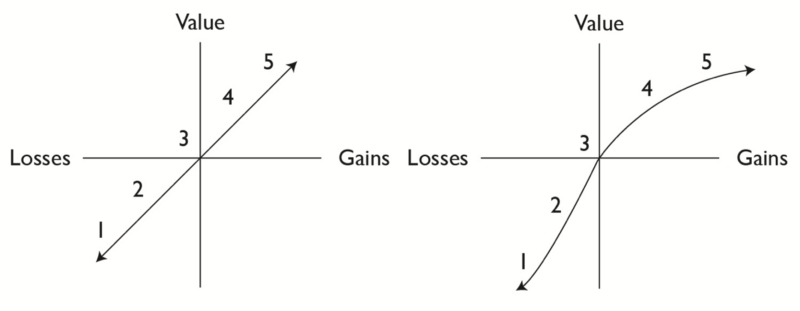

For hundreds of years, value was believed to be linear. An example of linear expected utility thinking would be to think that if I double my wealth, I double my happiness.

Linear function means easy to measure.

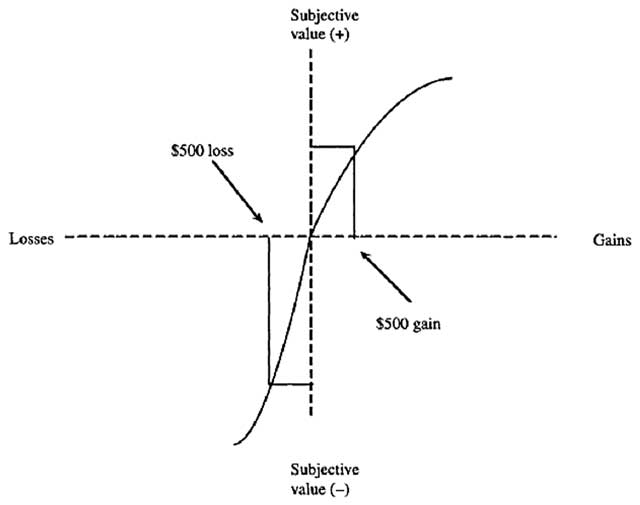

But as we now know, that isn't even close to being true, and value is distinctly non-linear.

Moreover, gains are calculated differently than losses.

We are actually relatively more sensitive to small losses than to big losses.

You can't really measure the emotions for each customer touchpoint with a ruler, so understanding this becomes much more complicated.

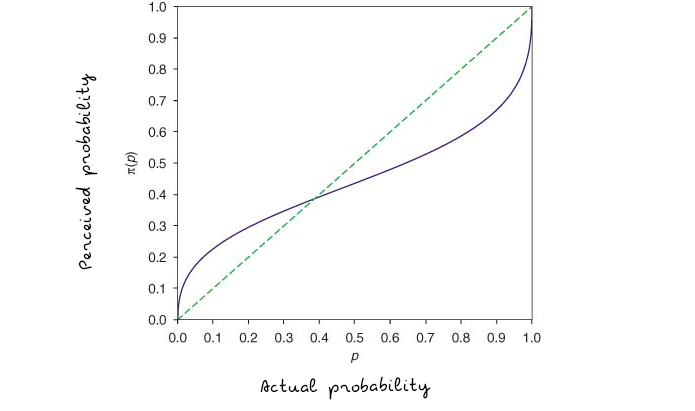

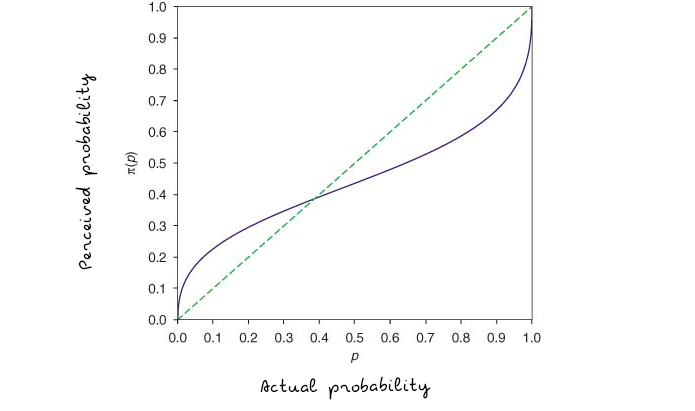

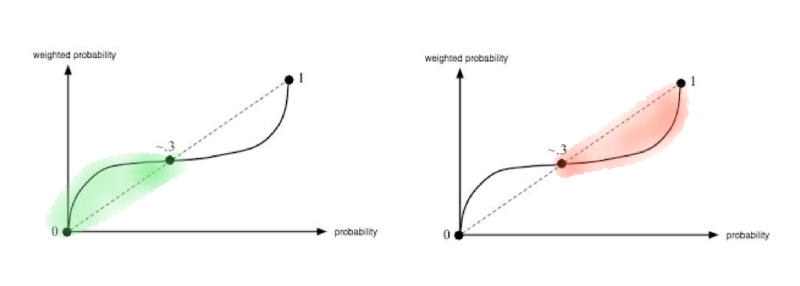

We also tend to react excessively to events with low probability (p <~0.3), and react less when they are most likely. (p >~0.3)

This means that unlikely outcomes are overvalued ("that will never happen") with the certainty of not getting them and very likely outcomes are underestimated ("that always happens") because of the certainty of obtaining them.

The chart above shows the typical prospect theory's probability weighting function, π(p), which is concave for small probabilities and convex for medium to large probabilities (and thus, consistent with the principle of diminishing sensitivity).

You have to deal with both of these phenomena: an event's probability and the customer's subjective value on one side, and the non-linearity of perceived gains/losses on the other side.

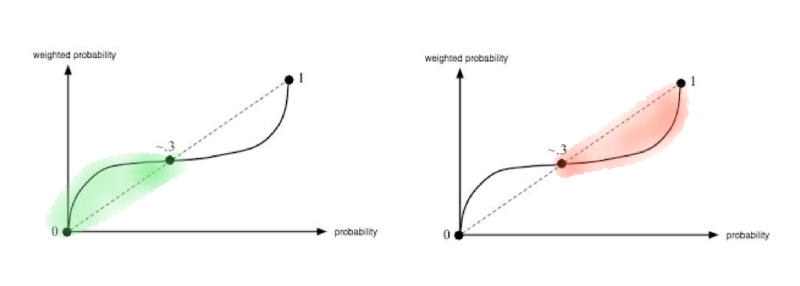

How does this translate to the customer journey? Along the customer journey, missing a step that the customer expects to happen can be disappointing for the customer, and quite harmful to their overall experience. Surprising that same customer with something he considers less likely to happen is proportionally more beneficial than you would expect.

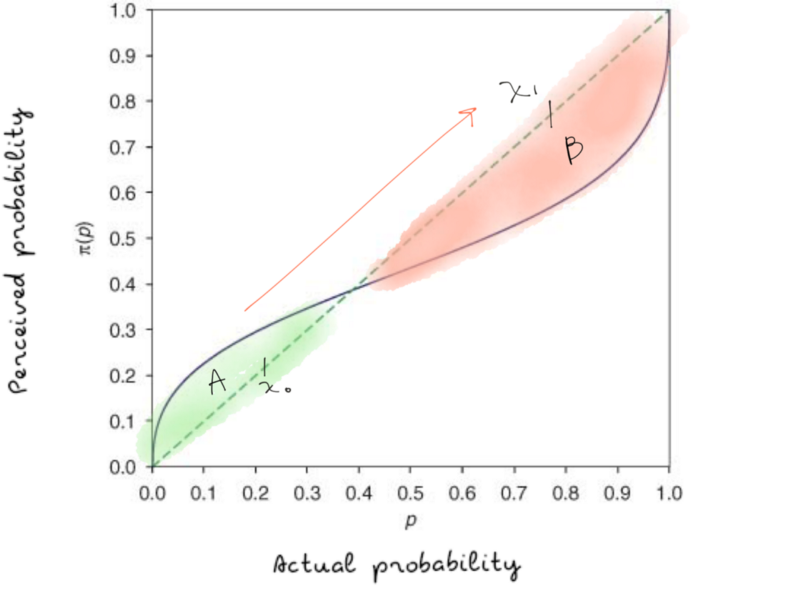

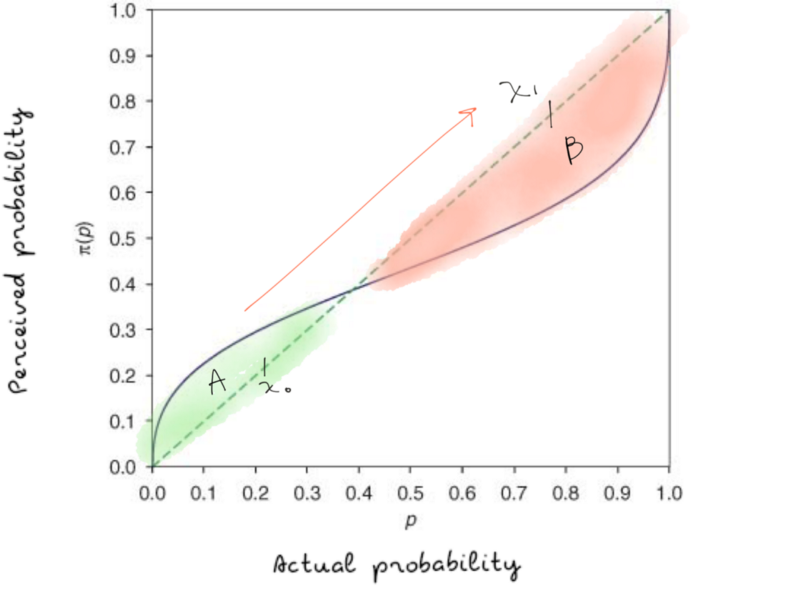

While most businesses play the game in the convex part of the subject evaluation function, they actually have a greater chance of surprising and delighting the customer in the concave part.

When mapping your customer journey, think about the opportunities you have to stay concave, to surprise and get proportionally greater gains. Then, think about what your customers expect, the things that, for them, are an obvious step in their journey. These are pitfalls where you risk losing credibility, and may be more harmful than you think.

An increase in the probability that a certain event will happen is a shift from concave to convex.

In marketing, we see this happen when a certain tactic gets formulated and applied on a larger scale. It ceases to be a positive and unexpected event (concave) and instead gets commoditized and translated on the convex part of the function where the perceived value is proportionally inferior.

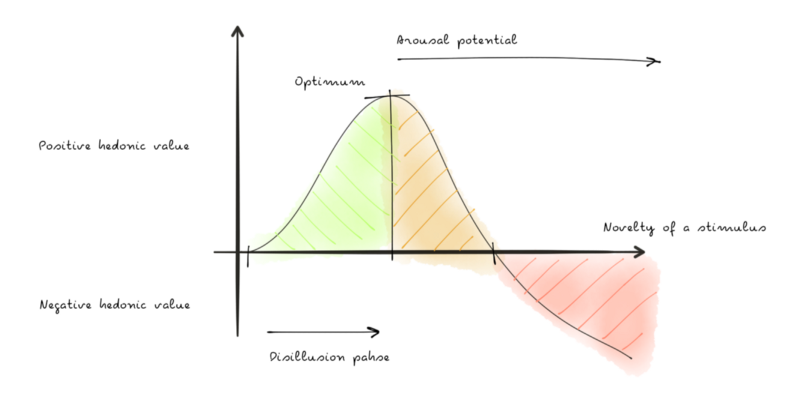

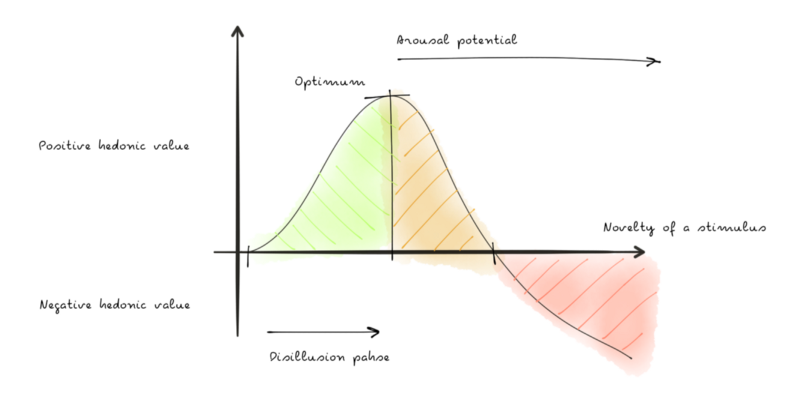

The specific fatigue that I'm talking about here is a translation between x0 ⊆ A (concave) and x1 ⊆ B (convex) has some common touchpoints with the Wundt-Berlyne curve.

When a stimulus is unlike anything encountered before, we are dealing with absolute novelty, and we experience pleasure. The hedonic value of a stimulus is regarded as a function, rising to a peak (optimum level of hedonic value) and then falling progressively to a disillusion phase.

The arousal is considered to be directly related to the novelty of the stimulus.

Every industry suffers from a certain fatigue that increases when something gets overused and saturates the market. This is valid for cinematic dramas, literature plots, aesthetic preferences, and even vocabulary used in common language. Marketing is no different.

Marketing (like many other disciplines) constantly needs new triggers to enable innovation and keep the arousal and the perceived hedonic value as high as possible. Tactics that are overused tend to dilute their effectiveness over time.

Example of concave opportunities for customer touchpoints

There are organizations that constantly work to innovate and keep customer arousal high and make sure they're exploiting the concave aspects of their customer's subject value function. Those companies strive to find new ways to keep constant triggers high and make sure their customers receive a delightful experience at every touch point.

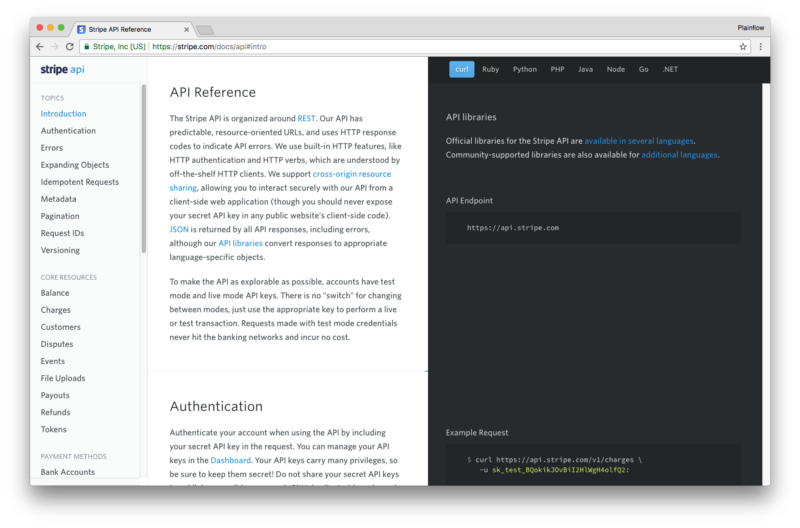

API and product documentation

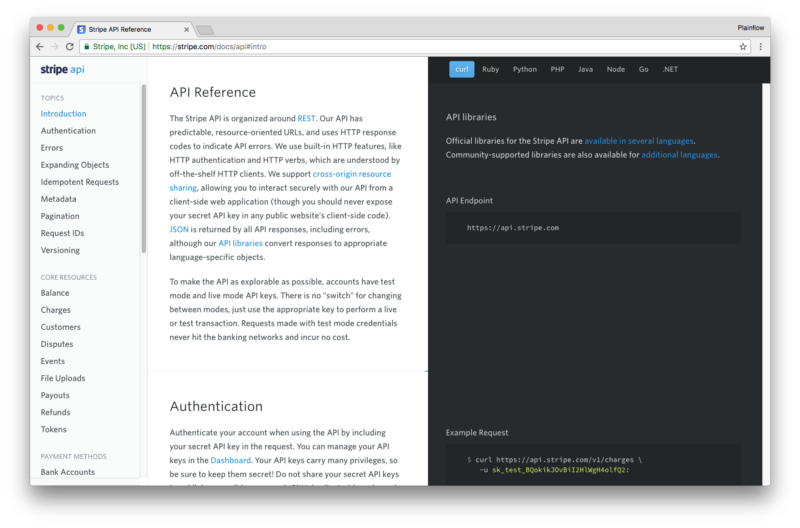

Before buying a software product, I always check out two things: the API documentation and the FAQs. Landing pages are designed to be attractive and charming for new visitors. Product and technical documentation are not.

Most of the time, API documentation and FAQs are meant to be useful for customers who are looking for integrations or to better understand the product. These are a much better predictor for product quality because they can tell you how much the company cares about their current customers.

Stripe is a perfect example (h/t Romain Huet). It changes the documentation based on whether you're logged- in or logged out. When you're logged out this is what you see:

They know that going back and forth between the API documentation and the application settings to grab the API key is a pain. That's why they magically display your API key directly in the documentation.

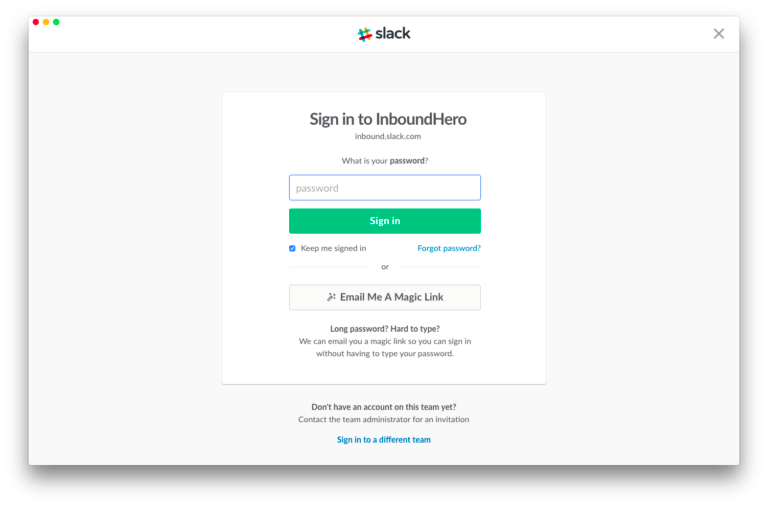

Login interactions

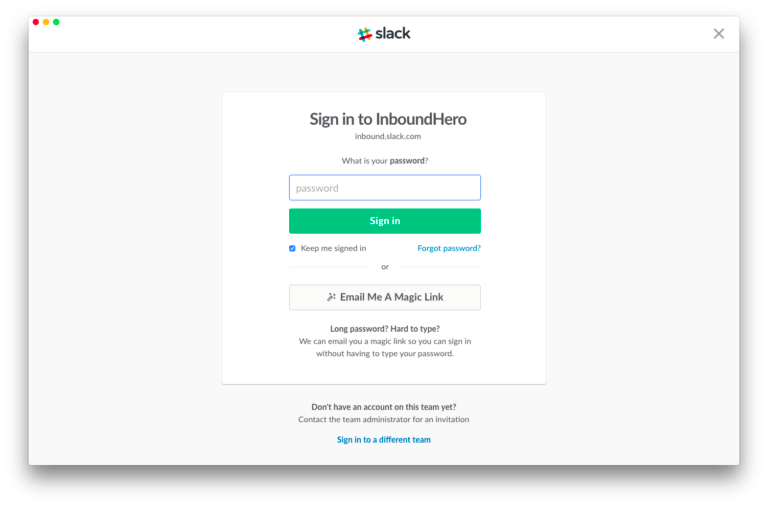

Log-ins are one of the most frequent actions for every SaaS product, yet they less likely to be exploited as an opportunity.

Slack realized that new users often do not remember their password after their first login, so they've found a way to give them a faster way to log in: The Magic Link.

In this interaction, Slack is playing in the concave playground of the customer's utility function where unexpected positive events trigger a burst in the customer's subjective value function, delivering proportionally greater satisfaction.

In a similar way, Mixpanel sends this email after a certain number of failed log-in attempts.

Favicons

Favicons are other spaces for concave customer touchpoints. In this case, Codeship (h/t Roman Kuba, Manuel Weiss, Moritz Plassnig) tells you what's the status of your build by changing the colors.

Handwritten email

If I had to choose five companies that are able to constantly surprise their customers, Product Hunt would be on the top of that list.

Product Hunt (h/t Ryan Hoover) is a major player in the concave area. The team has always strived to deliver a superior customer experience. Their way of surprising customers includes handwritten letters, stickers, t-shirts, socks, and much more. You name it, they've probably tried it.

API references, product documentation, FAQs, login interactions, fav-icons, 404 pages, and handwritten emails are only a few examples of concave opportunities for customer touchpoints.

On the definition of Customer Experience

To recap this post: we understood what customer experience is really about and why it's nothing new (but still very important). We explored the boundaries between perspective and psychology, and we analyzed the flaws and biases that drive perceived value and utility in the customer's mind.

Before leaving you, I want you to read one the best definitions of customer experience from Bernadette Jiwa in a Marketing: A Love Story.

Once when I was visiting a new city, I did a scout-around for a place that sold good coffee — it's usually the spot that isn't on the main street, the place where you see the locals hanging out. I took a chance, had a great experience and was on my way. The next day, I thought, 'why mess with success?' and headed back to the same café. The guy who took my order the day before asked if I'd like a … and he rattled off my non-standard coffee order from the day before. Boom, a shot of oxytocin and a feeling of instant connection and belonging.

I don't know how this guy ended up being 'that guy who remembers people by their coffee orders', but I bet his boss is glad that he did.

Be the one who is patient enough to take the time to make the customer feel like they belong. If you're in this for the long haul, you don't need the so-called shortcuts that will magically deliver more people to your door today.

Also, while there's a lot to learn from competitors and others who are doing customer experience right, your customers, and their journey, are probably different. What's concave for their customer might be convex for yours. Think about what might be concave and convex for your customer's subjective function and start with that when thinking about journey mapping.

To put in layman's terms, for the people you want to serve, you've got to find a way to be the guy who remembers people by their coffee orders. Surprise, delight, and repeat every step of the way.