From asymmetry to symmetry of information in the sales process

Sometimes marketers trick themselves and fall in love odd definitions. You've probably heard that "help is the new selling," as if it's something new. But is it, really? Isn't this what salespeople have been doing since … ever? Isn't "helping people" at the core of selling? In thinking about this, I've had a chance to think about how the role of sales is changing.Something has changed and it's continuously evolving over time, only it's not the helping per se. What has changed is how salespeople help.

To better understand this idea, let's step back to more than 50 years ago. In 1967, George Akerlof, a first-year assistant professor of economics at the University of California wrote a 13-page paper about the shady and somewhat misunderstood used-car market.

With only a handful of equations and economic theories, he touched a field where–quite curiously–no one had really delved in. Information distribution from parts when negotiating a deal.

After being rejected by two notoriously famous economics journals because they "don't publish such trivial stuff," three years later, the QJE (Quarterly Journal of Economics) accepted his theory and published the paper with enthusiasm: "The Market for Lemons: Quality and Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism." Thirty years later, George Akerlof won the Nobel prize for Economics.

If anyone isn't familiar with the Lemon Market problem, here it is in layman terms.

Imagine a used car market for second-hand vehicles that vary significantly in quality. Some cars work just like new (the "peaches"), and some are junk (the "lemons").

However, it's difficult for a buyer to determine the difference in a brief inspection.

In fact, peaches and lemons may be indistinguishable for most buyers. Because the buyer doesn't have perfect information, the seller can exploit this and charge them a price that is much higher than the actual value of the car.

Hence, there is a strong asymmetry of information between buyer and seller.

Suppose the true value of a good car (peach) is $1,000, and that of a lemon is only $500.

Only the seller knows if the car is a lemon — the buyer doesn't. Hence, a rational buyer, knowing that it could be lemon, may only be willing to offer $800 for the car.

This means that the only sellers who should accept this offer are the ones selling lemons: if you know the car you're selling is a peach and worth the full $1,000, you wouldn't sell it for less.

This creates a pernicious cycle: those with peaches will withdraw from the market, leaving a higher percentage of lemons, which in time should lead buyers to make ever-lower offers when buying a used car.

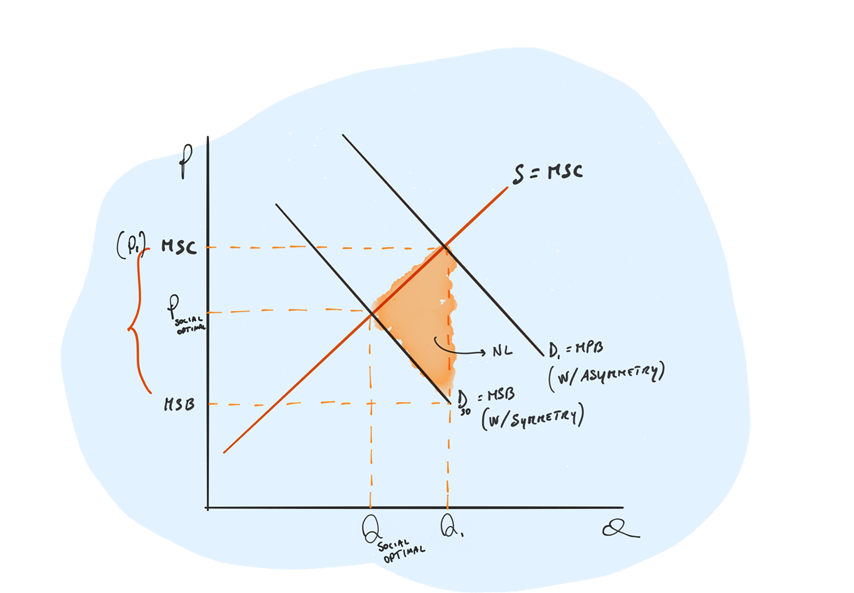

The core insight of the Market for Lemons problem is that asymmetric information between buyers and sellers disproportionately hurts the high-quality . Over a long enough time period, lemons will out-market peaches. And this will lead to a failure in the market when the provision of a good in a free market takes at a level that is greater than or less than the socially optimal level. (MSC>MSB)

If information was symmetric (Demand curve D social optimal), then the buyer and seller would have the exact same information, and the market would have been efficient in allocating the right price (P social optimal) and right quantity (Q social optimal). The price surely should have been lower (p2 < p1) because the consumer would have known that the car isn't a peach, and hence, asked for a lower price. The consumer may even have walked away.

The nature of the lemon market problem expresses itself whenever there's an individual transaction of two or more counterparts where one–with full access to information–is selling a good and the other–with partial access to information–is buying it.

Akerlof's simple idea recast how economists reasoned not only for individual transactions but for entire markets.

The paper offered one solution: warranties. If the buyer is offered a warranty on their car purchase, they'll have the confidence to pay the full $1,000. This would also re-invite the sellers with good cars back into the market. As a result, state legislatures started to pass "lemon laws" and brands started to provide customers with an assurance of quality, but that's another story.

In Akerlof's world, the more information the seller would have exposed to the buyer the more he would have helped the buyer.

buyer gap

In a world heavily distorted by information asymmetry, the "help" that salespeople could provide was "informing" their potential customers to put them in the condition to make the best deal.

When knowledge isn't equally distributed, it's helpful to have someone willing to share this information with us.

Now, try to recall the last time that you bought a vacuum cleaner from the mall, your last eBay purchase, or the last time you ordered a book from Amazon? Try to recall the last that you chose a restaurant to go out for dinner? Or even the last time that you bought a SaaS product online?

Before placing your eBay order you probably checked other buyer's review and the reputation of the seller. Before purchasing a new book on Amazon, you may have checked the reviews on Goodreads to make sure it was in line with your tastes.

Before even entering a restaurant most of us check for ratings and comments on sites like Yelp. Before purchasing software products we look for reviews and opinions from people in our network or from companies who are already using that particular solution.

The information gap is closing more and more every year. We're transitioning from a strong asymmetric world to a much more information symmetric world where everyone has access to the same amount and quality of knowledge.

Today, seller's knowledge is much more similar to buyer's knowledge. When we approach the sales guy, it's likely that we have already done our homework, and therefore have a solid opinion of the product we're about to buy.

In the past, having access to information and being able to wield it was what often determined success. Today, information is ubiquitous, and it's much less valuable.

So, if it's not the amount of knowledge that makes a difference, how can today's salespeople be successful?

Suppose that we are in the market for a new vacuum cleaner.

We've already done all of the research. We checked out the best review site and compared the best prices. We've asked our friends and co-workers to know which make and model they use. By the time we're ready to buy, we probably have a good idea of the alternatives available to best suit our requirements. We don't need the help of a salesperson.

That is, unless we're addressing the wrong problem.

The reason we're buying a vacuum cleaner, after all, is to use it to clean our home. But what if the real problem is that our window screens are doing a poor job of keeping out dust? Or maybe our carpet is the real issue (it's old, stained, and dirty). In this case, replacing it with a new one could partially solve my problem.

What if our real problem is that we don't have time to clean (and purchasing a vacuum cleaner only serves to make us feel better)? A cleaning service that can come in and clean our house once a week would solve this problem.

Having the right answers is not what is helpful. Having the right questions is what we value.

Problem finding is a creative activity that precedes problem-solving, which assumes competence in:

- challenging assumptions

- refraining from always obeying orders and rules

- attitude to new ideas

- negating the "formula" as a problem-solving method

There are three steps essential to effective problem finding:

Everything is linked directly or indirectly to something with similar qualities or to ideas that bear the same thoughts.

In examining the interconnection of things, we can see the problematic case and its relation to other variables.

The idea here is not to settle on the first problem that emerges as a result of a hunch. Thinking that the buyer has identified the problem, we will spend all of our energies putting into operation a solution that worked for a previous problem.

In exploring possible and alternative problems, the seller needs to ask a variety of questions such as those that look into the interconnection of things, the motives behind actions and intents, perceptions against reality. And thus explore the many factors that interconnect with the problematic case.

After wielding all of the possible questions without intending to answer them, the seller now selects the best alternative question or the 'right' question–the one question that gets at the heart of the problem, and that may then burst into a number of interconnected problems.

#Conclusion

We're biased to think that answers matter more than questions, that understanding a solution is more important than understanding a problem.

The closing information gap between sellers and buyers is a demonstration that this paradigm will change.

Yesterday's salespeople were skilled in giving the right answer. Today, salespeople need to be trained in asking the right questions, uncovering possibilities, and surfing latent issues. By going deep, they're able to find the right problems to solve.

Today's selling depends more and more on the creative, heuristic problem-spotting skills of artists rather than on the reductive, algorithmic, problem-solving of technicians.