Picasso, Schoenberg, Moss: how humans unlock social capital

(See HN thread here.)Once every while I read something that changes my perspective on things. Usually, not because it reveals a ground-breaking truth, but because it helps me connect the dots backward. Suddenly, things are now integral parts of a larger picture and everything makes more sense.

A year ago I read this piece from Eugene Wei: Status as a Service.

Eugene writes:

Why does proof of work matter for a social network? If people want to maximize social capital, why not make that as easy as possible? As with cryptocurrency, if it were so easy, it wouldn't be worth anything. Value is tied to scarcity, and scarcity on social networks derives from proof of work. Status isn't worth much if there's no skill and effort required to mine it. It's not that a social network that makes it easy for lots of users to perform well can't be a useful one, but competition for relative status still motivates humans. Recall our first tenet: humans are status-seeking monkeys. Status is a relative ladder. By definition, if everyone can achieve a certain type of status, it’s no status at all, it’s a participation trophy.He continues:

Read Twitter today and hardly any of the tweets are the mundane life updates of its awkward pre-puberty years. We are now in late-stage performative Twitter, where nearly every tweet is hungry as hell for favorites and retweets, and everyone is a trained pundit or comedian. It's hot takes and cool proverbs all the way down. The harmless status update Twitter was a less thirsty scene but also not much of a business. Still, sometimes I miss the halcyon days when not every tweet was a thirst trap. I hate the new Kanye, the bad mood Kanye, the always rude Kanye, spaz in the news Kanye, I miss the sweet Kanye, chop up the beats Kanye.Then, goes:

So, to answer an earlier question about how a new social network takes hold, let’s add this: a new Status as a Service business must devise some proof of work that depends on some actual skill to differentiate among users. If it does, then it creates, like an ICO, some new form of social capital currency of value to those users.

This didn't just resonate with me. It helped me understand on a deeper level how and why visual arts, aesthetics, music, and human taste in general develop.

Let’s start from the ground up.

In a few words, the article states that:

- Social Networks to thrive need a proof of concept

- Prohibitions spark human creativity in a newly formed area

- Humans, then, leverage that creativity to attract social capital and compete against each other in the newly formed arena

The more we understand a system, the more effective we are at allocating social capital in it. Hence, we need new restrictions to unlock new human creativity and feed new social capital back into the system.

This can explain on some levels how Social Networks develops, but I wondered what else? Are there are other fields where this theory applies just as well?

1. Painting: Cubism

For centuries, visual arts was one of the major arenas where human intellects competed. For centuries, humans challenged each other by representing reality through mere copies of the same instance.

And gradually, we were able to go from this..

To this:

Connects the dots and see how linear was the progression in the aesthetic. Over time, humans became quite extraordinary at this exercise.

Renaissance, impressionism, pointillism, abstract expressionism, realism, etc, were all micro-steps part of the same bigger effort: representing the reality for what it is.

Social capital in that area was progressively getting allocated up to the point where there was no much left to. Over centuries of incremental progress, we got the point where we mastered the proof of work.

So, we needed a radically new thing. A new greenfield and new proofs of concept.

Introducing cubism.

Unlike any of the prior movements, cubisms challenged the fundamental rules, the basic assumptions upon which the system was constructed. Reality should be represented as it is.

This new proof of work emphasized a flat, two-dimensional surface. It rejected the traditional techniques of perspective, foreshortening, modeling, chiaroscuro, etc, and refuted time-honored theories of art as the imitation of nature.

For the first time in history, painters were not bound to copying form, texture, color, space, etc. That was too well understood. They were called to present reality in radically fragmented objects, whose several sides were seen simultaneously.

The movement was pioneered by Braque who made the original proof of concept but it was Picasso who really extracted much of the social capital that came out of it.

2. Music: Dodecaphony (or Twelve-tonic technique, or Chromaticism)

First, Bach, the real explorer of Classic composition.Then Mozart, and Beethoven.

Then Chopin, Debussy, and Ravel.

Different styles emerged across centuries (from Baroque to Late Romantic) but the ground rules in the classical composition didn’t really change.

Let me explain.

In traditional Western music, tonality is a means of organizing pitch in accordance with the physics of sound. A fundamental tone — say, C in a C major scale — is central; the other pitches relate to it in a hierarchy of importance based on natural overtone relationships. So, whatever happens, the music keeps returning to that fundamental tonal mooring.

This is such a key aspect in music because it provides a sense of arrival and rest.

All Western classical and pop music relies on the idea that, no matter what, we'll eventually get to "home base".

Leveraging this musical axiom, musical composition techniques that had been prepared over centuries made it possible in the 18th century to write music that was original and immediately appealing but also sophisticated under the surface.

And by the end of the 18th century, a lot of low-hanging fruit was picked and much of the social capital in the system was already allocated in the hands of few. There wasn't much left to discover.

In 19th-century composers, Wagner, Mahler, Debussy, originality frequently came at the cost of greater surface complexity, and a less direct, cheerful tone.

It was clear that humans needed new ground-up rules to compete.

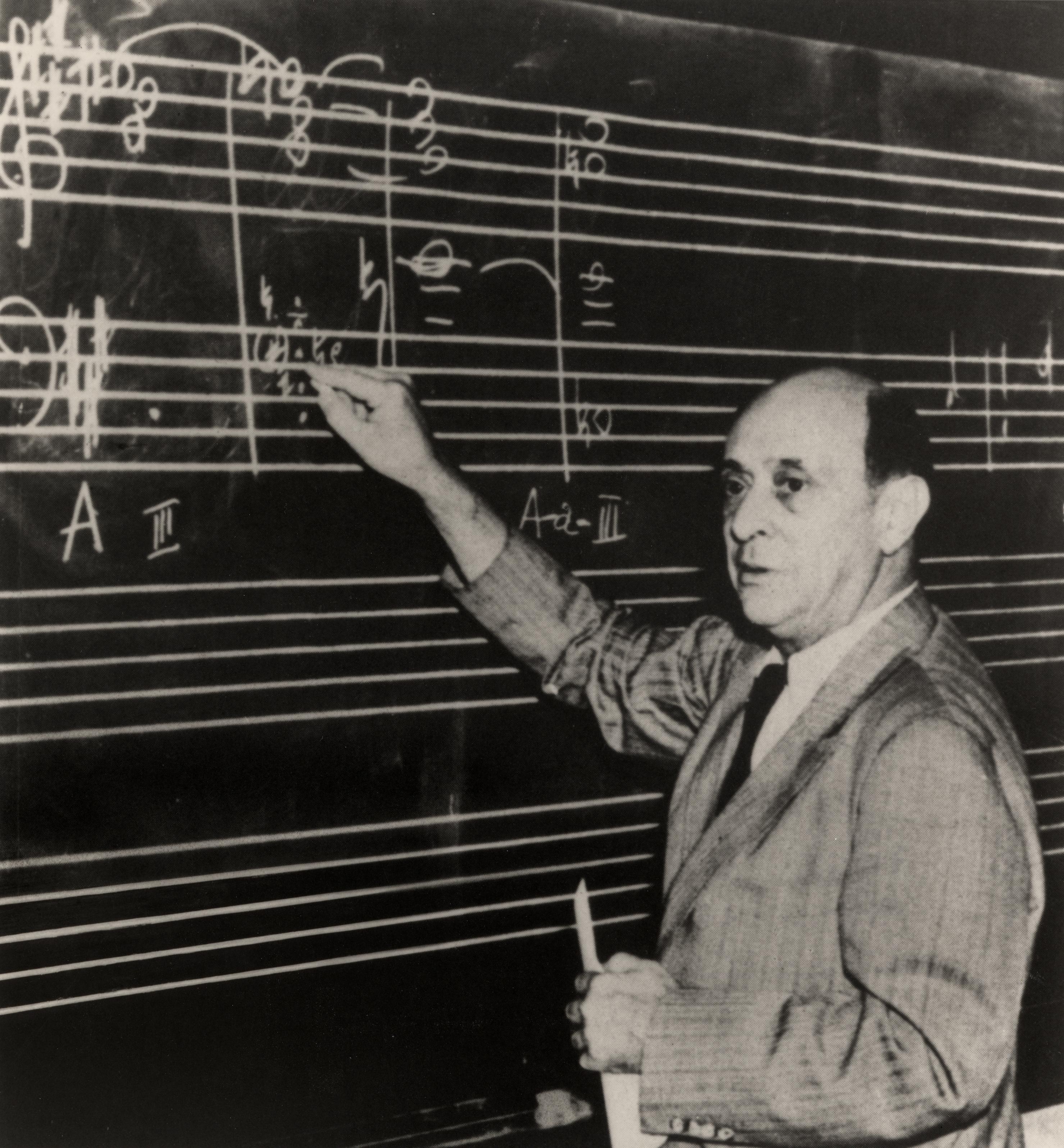

Schoenberg was one of the first to realize that new innovation could only be unlocked by re-thinking the ground-rules. So he invented a new compositional technique: twelve-tonic.

Shoenberg's twelve tonic technique comes with no musical tonality. All 12 pitches of the chromatic scale are sounded as often as one another in a piece of music without emphasis on any specific note. In other words, all 12 notes are thus given more or less equal importance, and the music avoids being in a key. Consequentially, there can't home base.

It was a radically new game.

Shoenberg's new musical arena unlocked new social capital and many of the composers of the 20th century competed on those new rules.

Several giants explored the 12-tone technique as well: not only Stravinsky, whose move into the enemy camp shook up the world of modern music but also Messiaen and Copland.

Looking backward, we can say the invention of the 12-tone system was arguably the most audacious and influential development in 20th-century music.

3. Fashion: Kate Moss

The world of the 19th century was a world in which the canons of beauty were sculptured.

Up to the point where the whole fashion scene was dominated by the same characters: Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell, Sharon Stone, etc.

That was a solved game.

It was in that world, that Corinne Day discovered a new way to represent beauty.

Not through the canonical blonde/long hair, nor the perfect-looking skin or the mesmerizing white of the teeth.

C. Day used the cheeky expression of a 16yo suburban skinny girl named Kate Moss to show the world an entirely new idea of aesthetics.

Way far from what were the conventions of the time.

Not colorful, but black and white photos.

Not sinuous, but skinny body forms.

Not perfect-looking, but seemingly sloppy dresses.

Not cheerful, but melancholic tones.

It was a totally different game with totally different rules.

The effects were immediate. Existing players were outplayed, new social capital was unlocked, and new icons emerged.

Moss did to Campbell, what Braque did to Manet, and what Shoenberg did to centuries of Mozart.

Centuries of slow but incremental linear development lost in a matter of a few years.

Visual arts, philosophy, music, and many realms get periodically rearranged according to the same principles: when there’s no more Social Capital left on the table either because it eroded over centuries or because it was consolidated in the hands of just a few winners.

After all, we're all are status-seeking monkeys seek out the most efficient path to maximizing social capital.

Others essays to further explore this topic: